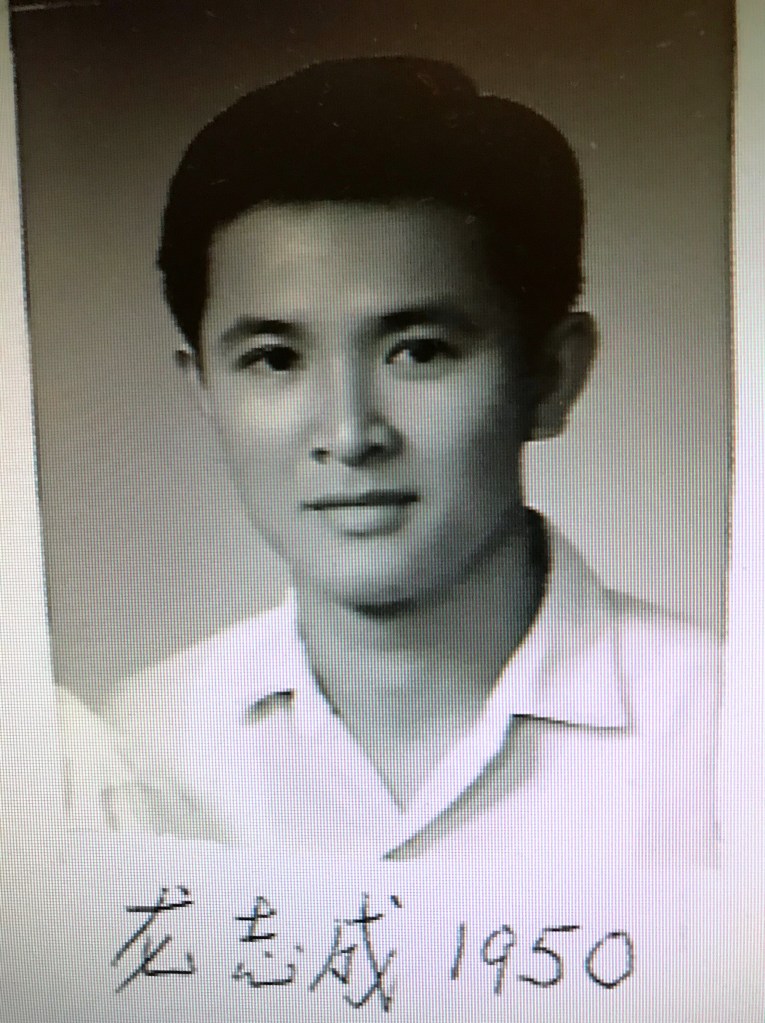

Author: 龍志成 Leong Chee Seng

Revision to WP Block 31 July 2021

We, Leong Siew Ting (梁壽廷), Tham Siew Kai (譚韶佳), Chow Kat Wah (曹吉華) and I (龍志成), were the first batch of graduates from Kuala Belait Chung Hua Primary School, after the second World War.

After graduation, our parents sent us to further our education in Nanjing, China. It was then quite an unusual move. The usual pathway for further education was to enroll in one of the English middle schools – St. Thomas’s or St. Joseph’s in Kuching, Sarawak, leading to the Cambridge University Oversea School Certificate. Another option was to continue our Chinese education in one of the Chinese high schools in Singapore.

The idea that we should venture to such a distant land was mooted by our School Principal, Mr. T S Sung . He talked to my father that I should continue my Chinese education in China. We were told Siew Ting’s elder brother, Mr. Leong Shau Fang who was a civil engineer employed with the Ministry of Works and Commerce in China, would take care of us including enrolling us in an established high school. Furthermore, Siew Ting’s eldest brother, Mr. Leong Shau Nam, kindly offered to pay for the cost of the trip first, and my father would repay him by installments.

At first my father was apprehensive. He was employed with Brunei Shell Petroleum as an auto-electrician, and had to take care of eight in the family. If an untoward incident happened, he would not have the financial resource to deal with it. On the other hand, I thought it was exciting. Although the only travel I had was a short trip to Miri arranged by our school football team, I naively had no fear. Chinese proverbs had it that a newly born calf is not afraid of the tiger. Eventually my father agreed to take up the challenge.

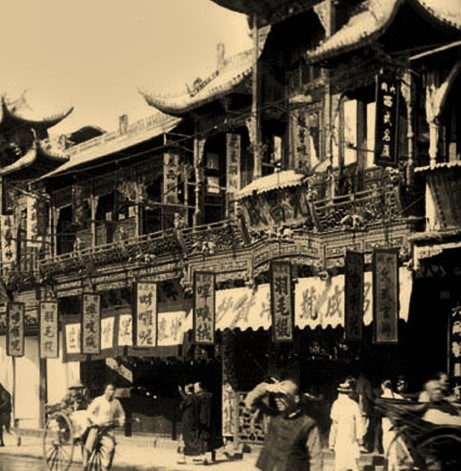

Thus on the 22 of July 1948, four of us, all at sixteen years of age, set off for China. We traveled from Miri to Singapore by a cargo/passenger ship, arriving in Singapore on the 25 of July. After staying in Singapore for five days, we boarded another cargo/passenger ship bounding for Shanghai. The journey took nearly two weeks, including stopping at Hong Kong for five days to discharge cargoes and take on new assignments. Arriving in Shanghai, we were relieved that Siew Ting’s brother, Fang Ko, was there to meet us. We spent the night in Shanghai and then boarded a train to Nanjing the next day.

We then enrolled in Dong Fang Private High School in early September 1948. Because we were late to enroll, they placed us in the branch campus. The school had already entered the first half of second-year term, and with our primary school diploma, they would not permit us to join the class. Fortunately, before setting out for China, we attended six months of preparation class, after completing our primary school, and that the school authority recognized and they permitted us to join the junior middle second year class. We had no problem with our school lessons though, especially English in which we were well ahead.

The branch campus was quite a small school, comprising only one building and on the city fringe, about five kilometers from the city centre. The main campus was in the city, and had much better facilities. We hoped to get a transfer to the main campus in the following year. Another option was to gain entry to the high school affiliated with the renowned Chung Yang University in Nanjing.

Dong Fang Private High School was a reputable school. The teaching curriculum was similar to what we had in Chung Hua School. However, there was no organized sporting activities, apart from some free-hand exercises and running around the block, under the supervision of a teacher. School uniform was not required at the branch campus. School fee including boarding was comparable to that of St Thomas’s Boarding School in Kuching. In the beginning the meals provided by the school were very good. The menu often included chicken, duck or fish. However, within a couple months, our good living would soon shatter due to the civil war and inflation.

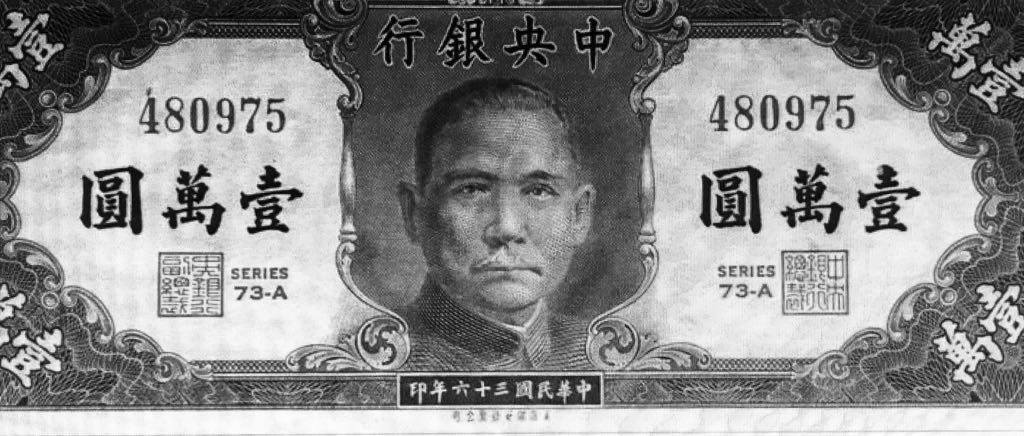

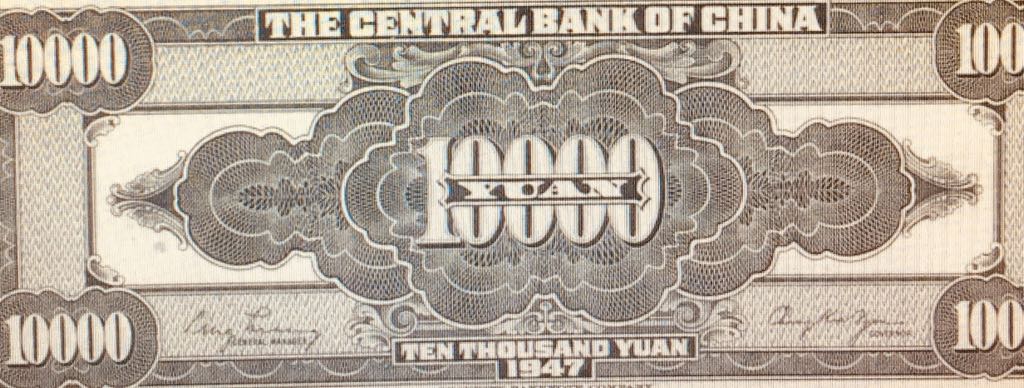

Before we went to China, the old Chinese currency had already been very much devalued. To supplement my meals, occasionally I liked to buy some salted peanuts to eat with my rice. One table spoonful of peanuts would cost twenty thousand yuan.

By early October that year, the old currency was so much debased by the inflation that the Nationalist Government decided to abolish it altogether. They proclaimed a new currency to replace the old. For a short time, the old currency could exchange for the new currency, but at a huge discounted rate.

Meanwhile the civil war continued with increasing ferocity. I could see more airplanes flying over our school towards the north, to support the Government troops fighting there. Refugees escaping from the fighting in the north, were pouring into our city. Staving and sick people were everywhere in the streets. I saw one elderly man with a young girl, kneeling on the side of the road begging for help. His face was drenching in blood from knocking his head umpteen times on the concrete path. They wrapped corpses in mats and just left on the side of the street.

The continuing civil war caused hyper-inflation. Prices of foods would double in a matter of weeks. Because of government corruption and rampant inflation, the Nationalist Government had lost almost all the provinces in the north. The war was moving closer to the capital, Nanjing. There were still a few boarders, including the four of us from Brunei, remaining in the Boarding School. The meals now were awful, comprising boiled rice scraps, rotten vegetable and worm infested salt fish. Cooking oil was at a premium and reserved for the few teaching staff who shared the same food with us. They merely had some oil added to their dishes.

They cooked our meals in a big wok on a large stove, fired by some dried grass which was collected from the nearby farmland. Coal and firewood were too expensive and very scarce. Piped water was available in our school but of doubtful quality. The water was icy cold, too cold for washing our face. The kitchen was warm, and we liked to make friend with the cook. Once we attempted to place our mugs of icy water onto the hot stove, when the cook was not watching. The cook of course saw through our little trick. He turned around and harshly told us to remove our mugs!

Winter in Nanjing was freezing. In the morning the ground around our school was covered with sheets of ice and frost. Our school was not heated, and without nutritious food intake for quite a while, our bodies were just not able to cope with the severe cold. We would sometime lie in bed for most of the day and night. Going to the toilet was a problem. The toilet was located in the adjoining farmland, some distance away from our school. It was just a trench dug in the ground inside a straw enclosure, and it stunk to high heaven.

There was no bathroom in our school. Public bathing facilities were available in the city but at a charge. The northern Chinese did not take their bath often. So following the local practice, we took our bath about once a month when we visited a colleague of Fang Ko, Mr. Wang, who lodged in the Ministry staff quarters. There was a common bath house in the ministry compound, and they permitted us to use the facilities. The visit also allowed us to receive messages from Fang Ko, who was managing our money, and in contact with our parents in Brunei.

By the beginning of winter of 1948, the Nationalist Government had lost its last stronghold, Xuzhou, and the capital was threatened. Defeated government troops were retreating back into Nanjing. Rumors spread that the city gates had been closed to prepare for the defense of the capital. We were now stranded.

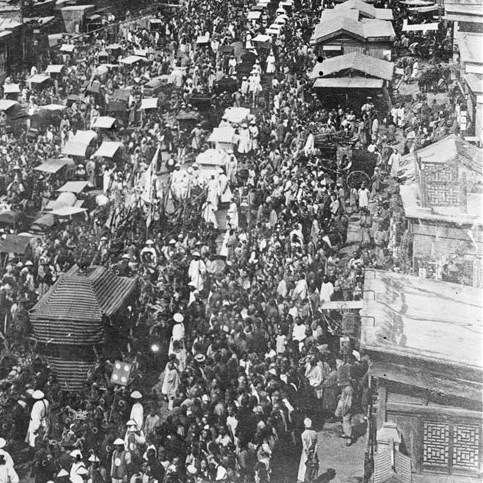

Fortunately Fang Ko managed to obtain four railway passes for us to leave Nanjing on an evacuating train, assigned to the families of staff employed with the ministry. It was mid December 1948. Our train headed towards Shanghai and arrived in Hangzhou, where we hoped to board another train traveling south. The station was thronging with a sea of people, all trying to escape from the imminent fighting. By and by, we caught sight of a train destined for Guangzhou, but it was full and packed to the ceiling. However we managed to climb into one of the carriages, and with some effort squeeze out four seats for us to sit on. It was so constricted that I hardly had room to stretch my legs. After some delay, our train began to depart. More refugees had climb onto our train during the delay. A number of them were sitting on top of the carriages. Those poor souls, if they did not fall off the moving train, would freeze to death in the night. Surely the next morning, we were told that someone had fallen off the top of our carriage.

After Hangzhou, our train was traveling towards Wuhan – an industrial city, and a major transport hub in central China. After passing Wuhan, it stopped for a long time in the middle of nowhere. Some people said that the Army had commandeered our train, or that the rail tracks ahead had been sabotaged by communists agents. Eventually much to our relief, it would start to move again and resume its journey to the south.

Food was not available on the train. We had to buy our own from the many hawkers plying the railway stations. Once we arrived at a seemingly large station, several hawkers were selling foods there. Some were cooking on hot stoves. It smelt delicious. It was too good to miss. So Siew Ting and I decided to descend from our train carriage. There was a crowd at the station, and we waited for our turn to place our orders. Alas, without warning, our train suddenly started to move out of the station. We ran for our lives to dash back to our carriage that by then had gathered some speed. Fortunately we managed to scramble onto the last carriage.

There were no toilet facilities on the train. When it made a stop on the way, we could see people running to the nearby bushes to relieve themselves. One lady and her escort went too far into the bush, presumably to safeguard their modesty. But when the train suddenly departed, they could not return in time to climb back into their carriage. Some good Samaritans tried to pull them back into the carriage but to no avail. They were left behind.

Our train had more unannounced stops on the way. Finally it willy-nilly reached Guangzhou. The whole journey took seven days. Normally the same journey should have taken about two days.

We arrived in Guangzhou, unkempt in our dirty and smelly blue Chinese long gowns, after not having had a haircut nor bath for the last couple of months. We were told to quickly have our hair cut in the nearby barber shop and bathe in the public bath house, before joining the office staff for dinner.

Our host was a university friend of Fang Ko. He had an office cum living space on top of a shop house. We were very well looked after. Life was leisurely and meals was very good.

Meanwhile Siew Kai had managed to make contact with his Uncle in Guangzhou and left us to stay with him and his family. While there he spent two weeks visiting his grandparents in the village during the Chinese New Year.

We stayed in Guangzhou for about one month waiting for our parents to decide on our next move. Finally we were told to return to Brunei and continue our study in Chinese High School in Singapore.

We boarded a train from Guangzhou to Hong Kong on the 22 January 1949. In Hong Kong we would try to find a ship to take us back to Singapore. Again Fang Ko had another university friend in Hong Kong, who would put us up in their residence.

Hong Kong Bay view from Victoria Peak

Our host was a wealthy man living in a condominium, high on the hill near the Central Business District. We were asked to join the family for dinner. Dinners were sumptuous and delicious, with servants in attendance. They well crafted the dishes of food. The rice was well formed, but in rather small bowls, as wealthy people did not eat much. The upshot was that we three uncouth young men had unwittingly devoured too much at the dinner table. We felt uneasy and thought we should not abuse their hospitality further. The next day we said to our host that we would be out most of the time to look for a ship to Singapore, and not joining the family for dinner.

We usually bought our meals from the food stores in the city. The foods were bland but cheap, and we could eat to our heart’s content. Then came Chinese New Year when all the shops and food stores in the city were closed. We had to screw up our courage to go to our host, and asked whether we could join the family for dinner again.

After wandering around Hong Kong for five days, we managed to buy three tickets on a scheduled cargo/passenger ship bounding for Singapore.

Clifford Pier, Singapore 1949

We arrived in Singapore on the 14 February 1949, and were in trouble again. Our passports issued by the Nationalist Government, were no longer recognized by the Singapore Colonial Government. Consequently, we were remanded behind bars in the immigration jail. The jailer, a Sikh , was a nasty man. He would not allowed us to make any phone call. We were helpless. After discussing among ourselves, we decided to offer our Sikh jailer a ‘tip’, locally known as ‘tea money’. Siew Ting was holding a fake ten dollar Hong Kong note we thought could be used for the purpose. Upon receiving our ‘tea money’, the jailer’s demeanor changed instantly, and allowed Siew Ting to go out to get help. Siew Ting managed to contact our travel agent who then sponsored us for entry into Singapore. Siew Ting and Kat Wah were born in Sarawak, a British colony just like Singapore. They were allowed to enter Singapore without hustle, except that their passports were retained by the immigration authority for the duration of their stay in Singapore. I was born in China and had to pay a bond at 500 Singapore dollars before being granted an entry visa. Fortunately I had an uncle in Singapore, who kindly loaned me the money to get me out of the immigration jail.

The upshot was we were now all out of trouble, and proceeded merrily to enroll ourselves in Chinese High School in Singapore. They permitted us to join junior middle second year.

In late 1951, Chinese High School was temporally closed by order of the Colonial Government which feared the spread of communist influence in the school. At the same time, armed police surrounded our dormitory early in the morning, with sub-machine guns at the ready, while detectives searched our dormitory. A few students were taken away for further questioning.

When the school reopened again, all students were subjected to a vetting process, and those who were allowed to re-enroll, were put on good behavior bonds guaranteed by their parents or guardians. Having gained my junior middle school diploma, I decided to return to my home town in Brunei, intending to furthering my education in one of the English schools in Kuching.

At the same time, Siew Kai who stayed back in Guangzhou, attended school at Sze Yit Hua Chiaw Middle School. After about three months, he too had to leave China to return to Sarawak, because his uncle and family had to evacuate to Macau. Subsequently he enrolled himself to study in St. Joseph’s School in Kuching.

We were grateful to Fang Ko who looked after us, and finally planned our escape from China.

We had endured harsh living conditions, and experienced hyper-inflation. We had witnessed the terrible suffering and misery of the people brought about by the civil war. For the hardship that we had gone through, it was a valuable experience overall.

Leong Chee Seng

June 6, 2018

From the desk of the Producer:-

Acknowledgment: Thanks to Tham Siew Kai, Chow Kat Wah and Leong Siew Ting for their valuable contributions, for me to make some of the amendments and to update some of the details that were omitted from my first draft.

Disclaimer: Some of the photos are from social media, some of the Images in this blog are copyright to it respectful owners. Please let us now if you have any issue with copyright, let us know and we will promptly remove it asap. Thank you.

文中圖片來自綱絡,如有侵權,請联繫刪除!

Reblogged this on KatChow.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wendy is my second daughter. She is the Head of Operation Strategy at the Aust. Gov. Future Fund, and is probably too occupied with her works to provide further comment. Elena is my eldest daughter. They both live in Melbourne with their husbands. Siew Kong is my younger brother of course. He and his wife reside in Miri.

I appreciate that they have taken an interest in my story. This is the first time I have provided a comprehensive account of my venture to study in China and in writing.

LikeLike

Thank you Chee Seng, we appreciate the clarification.

LikeLike

An excellent post about what must have been a harrowing time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Elena for commenting. We are very excited in your response to this actual account of 4 Brunei students’ journey. Hope you have your own story to tell and do encourage other KBCHMS alums to get involved.

LikeLike

Thank you Elena Leong for your comment. There are 2 Leong in this story, are you related to anyone of them?

LikeLike

Haha! I realize the confusion of my relationship to one of the LEONGs in the story ! I am the second brother in our Leong family of Leong Chee Seng ! We are Hainanese and our surname is DRAGON .. in Hainanese, it is pronounced as LEONG and so it was registered as such ! I was registered as LOONG ( in Mandarin). Chee Seng is the eldest in our family of 6 siblings. My eldest sister is Leong Siew Chiau ( residing in Sydney), then, Leong Siew Kai ( Melbourne) myself ( in Miri), then my youngest brother Loong Chee Ang ( who passed away in Montreal 4 years ago ). My youngest sister in Long Siew Ngoh ( Sydney). So in our family we have 3 different surnames due to carelessness in registration at birth!!

Yes, I went to KBCHMS but left after primary 4 to enroll in St Michael’s School Seria when our family moved from KB to Seria !

I worked overseas for some 20 years prior to my retirement in 2009 and feel Miri is still home! My overseas postings included 5 years in USA ( Miami ) 5 years in South America ( Georgetown Guyana ), 2 years in Singapore , 2 years in Taiwan ( Taipei ) and 5 years in China ( Kunshan, Yangzhou ,Shanghai and Nanjing ) and briefly in Cambodia !

PS: I think I know Chiew Chee Phoong. We were primary school classmates in KBCHMS !

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is an amazing account of my brother’s trip to Nanjing purely in search of further education and his lucky “escape” to come home. He and his young classmates must be very brave to take that path stepping into a war zone just to better themselves when such educational facilities were not available in Brunei ! My parents must be terrified when the war between KMT and CCP escalated as communication was almost zero at that time. I was an innocent kid and had no clues of the risks and hardship my brother had endured. Now, I know !

I had the opportunity to be in Nanjing on job assignments in 2000s. I did wonder the life contrasts of Nanjing in 1948 and 2004, some 5 decades later ! I was proud to tell my colleagues and Government officials in Nanjing that my brother was in Nanjing before me as student 56 years ago !

I strongly believe in fate. Thanks God, we are blessed with comfortable life now !

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Chee Kong for your comments. Perhaps you have your very own story to write? We welcome all KBCHMS alums to participate in our ebook.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Loong Siew Kong ( Chee Yoke ), What is the name of your brother who was in Nanjing 56 years ago? It would help us to understand better if you have a family photos or just your siblings? Did you study in Kuala Belait Chung Hua School?

LikeLike

Congratulations! 146 visitors read this story “Memories of our venture to China for further education” on the first 4 days of its release; it is one of the top popular publications ! Well done!

Comment from our Blog Administrator

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is an amazing and interesting story – quite an adventure! The hardships you encountered are hard to imagine. I look forward to the next episode to this story! Wen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Wendy Leong, thank you for your comment. Are you some how related to the Leong/Loong family? It is a good suggestion to continue the next episode but we need a lot of help from the Leong/Loong/Chow /Tham families to write and to share their own adventures or their stories. Would you like to come forward and help?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Chee Leong commented on Memories of our venture to China for further education. in response to chowkat:

Wendy is my second daughter. She is the Head of Operation Strategy at the Aust. Gov. Future Fund, and is probably too occupied with her works to provide further comment. Elena is my eldest daughter. They both live in Melbourne with their husbands. Siew Kong is my younger brother of course. He and his wife reside in Miri.

I appreciate that they have taken an interest in my story. This is the first time I have provided a comprehensive account of my venture to study in China and in writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on KatChow.

LikeLike

Hello Uncle Chee Seng ( Elena and Wendy). What an incredible opportunity and experience you were given. Through war, famine and detention, it is quite remarkable that you survived to tell the tale. I’m so happy that you and your friends did.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Yin Ching, thank you for your comment. I understand that Uncle Chee Seng is under the weather and he might not go online to reply your comment. There please call him directly to his family and express your comment? Please send him my best regards.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Yin Chin for reading my story and your comment. I was then just a greenhorn , like a newly born calf not afraid the tiger. Anyway, it was quite a valuable experience overall.

LikeLiked by 1 person