AUSTRALIAN SCHOLARSHIP AWARD

In 1955, after studying for five years at St. Thomas’s School as a boarder in Kuching and having sat for my Cambridge University oversea school certificate examination, I was all set to leave school and return to Brunei to seek employment, but my boarding school housemaster, Mr. Leefe, thought otherwise. He said the Sarawak Government was calling for applications for the Colombo Plan Scholarships to be awarded by the Australian Government to study at an Australian university and thought I should apply for the scholarship. Seven scholarships were offered, one for Engineering, one for Medicine, one for the Law, one for Veterinary Science, and three for Education. But I believed I was not eligible because I was not a Sarawak resident. Yet my housemaster was adamant and insisted I filled in an application for him to submit it on my behalf. I complied with his advice of course and chose Engineering as my course of study, but expected little chance of success. It later turned out that my housemaster was right. He was wiser than I and to him, I was most grateful.

Meanwhile, the Cambridge University oversea school certificate examination results had arrived, and I gained five “Very Goods” and awarded a First Division Certificate that was an excellent result unprecedented in the history of St. Thomas’s School.

St Thomas’s School Logo

St. Thomas’s School Kuching

Following my application for the Colombo Plan scholarship, I was shortlisted to attend an interview in front of a panel of four senior government officers. Nonetheless, by the end of the year, I would have to leave Sarawak before my travel visa expired.

I returned to Brunei and found the employment prospect grim. The only well-established company, Brunei Shell Petroleum Company, was winding down its operation because of the depleting oil reserve. Still, I applied to Brunei Shell for any possible job opportunity. Subsequently, I attended an interview with the personnel manager of the company and to my surprise, I was offered a position as a trainee in the paleontology laboratory, an important unit in the exploration and production of oil and gas. The laboratory was staffed by highly qualified paleontologists. There were also two other trainees who joined the company before me. My training initially was to examine and pick out tiny fossil fragments under a microscope. We also attended lectures on fossils and the geological formation of the earth, given by the laboratory specialists.

Lo and behold! The Sarawak Government now in a letter informed me that I had been nominated for the Colombo Plan Scholarship to undertake a course of study in engineering at an Australian university in Australia. Furthermore, I was required to continue my schooling in Form Six while waiting for my nomination to be approved by the Australian Government. Thus, I resigned from my position with Brunei Shell after only being in the employ of the company for just over one month. I apologized profusely to my employer for the inconvenience I had caused.

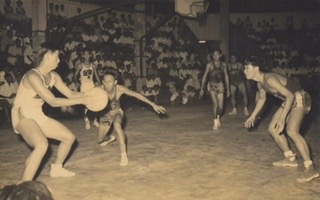

The Australian Colombo Plan scholarship was a highly competitive scholarship, and the selection was based on merits. Looking back, I did achieve an outstanding result in my Cambridge University oversea school certificate examination. At my school, I was at the top of my class, a senior prefect, the secretary of the debating society, and a member of my school debating team taking part in inter-school debates. I was active in various sports and selected to play for the Kuching Basketball Team to take part in South-East Asia Basketball Tournament in Singapore. All these had probably contributed to my success in being awarded the Australian scholarship.

St. Thomas’ vs North Borneo All Stars, 1954

SE Asia Basketball Tournament in Singapore Stadium, 1954

After leaving my employment with Brunei Shell, I traveled back to Kuching. However, to resume schooling at my former school, I had to secure a job to support my living. Fortunately, my former school headmaster, Mr. Song Thiam Eng, readily offered me a part-time teaching position at St. Thomas’s School, teaching mathematics for six hours a week. In addition, I also managed to get a job as a teacher in the adult education night school working three nights a week. Now the money I received was sufficient to pay for my living expenses. However, my headmaster wanted me to take three more classes teaching Form Two and Form Three algebra and geometry. I felt obliged because of the trust my headmaster had in me, but my Form Six science teacher was critical. He noticed I had missed so many of his classes and my class work was falling behind. I promised to work harder to catch up on my class works.

Meanwhile, my mentor, Mr. Leefe, had left St. Thomas’s School and returned to England to commence his priesthood training, and a Father Marshall was now the boarding school housemaster. Father Marshall said to me he regarded me as a teacher, and could no longer let me stay in the boarding house. I felt a sense of deja vu, being a non-Christian studying in a Christian school. Fortunately, a distant relative kindly accepted me to board with his family while I was studying in Kuching. I moved out of the boarding house which had been my home for the last five years, with a feeling of sadness.

By the last quarter of the year, I was advised by the secretary of the scholarship committee, who was a senior administrative officer in the State Secretary Office, that my nomination for the Colombo Plan scholarship had been approved by the Australian Government. I would be traveling to Melbourne to undertake a degree course in civil engineering at the University of Melbourne. But prior to that, I would have to attend a pre-university year and pass the matriculation examination for admission to the university.

Now it transpired that I was a not a citizen of any country – a “stateless person”, and only permitted to remain temporarily in Sarawak until the end of the year. Thus, the Immigration Department would not issue me any travel document for traveling to Australia. The secretary of the scholarship committee was in a foul mood, chiding me for not having raised the issue earlier. He darted out of his office while I sat sheepishly waiting for my fate to be determined. When he returned, he told me that I would have to apply for “Naturalisation” to become a British citizen and meanwhile I would be issued a Certificate of Identity for travel to Australia.

DESTINATION AUSTRALIA

On the 28 December 1956, I together with six other Colombo Plan Scholarship students set out for Singapore en route to Australia. In Singapore, the Australian Government was very generous to put us up at the Raffles Hotel, which was a premium hotel for the dignitaries and celebrities.

I shared a large room with another scholarship student. My first experience of the high-society life was a bit of embarrassment. Our room had an en-suite bathroom and was beautifully decorated. It had two large beds both covered with exquisite bedspreads with two fresh pillows. Being air-conditioned, the room was cold in the night but we could not find any blanket. The next morning, the room-service man came to service our room and was wondering whether we slept in the beds at all last night. We said we could not find any blanket. He then removed the bedspread to expose a large wool blanket over two layers of smooth bed sheets on top of a thick mattress. He said we were supposed to sleep under the blanket and in between the two bed sheets!

The following day, we boarded a Constellation aircraft flying from Singapore to Sydney, all paid for by the Australian Government. Upon arrival at the immigration check-point, my immigration status again came back to haunt me. My Certificate of Identity issued by the Sarawak Government was not acceptable for entry into Australia. It was the time of White Australia policy, under which no non-white was permitted to settle in Australia. Consequently, I was detained at the immigration check-point. Meanwhile, the officer from the Australian Foreign Affairs Office who was there to meet us found that he had one scholarship student missing and came back to investigate.

The immigration officer was questioning why my government gave me a scholarship but would not issue me a passport. However, the officer from the Foreign Affairs was quite forceful and asserted that I was a guest of the Commonwealth (Australian) Government and he could not leave me there. Anyway, he would take the responsibility and have the problem sorted out later. Having said that, he signaled to me to leave and walked out of the immigration office with me in tow. Fortunately, this distressing episode of my life would soon have a favorable ending. Subsequently in Melbourne, the British High Commission informed me that my application for British citizenship had been approved together with a British passport. Hallelujah! Thanks to the Sarawak Government, I was now no longer a “stateless person” to be treated like a pariah by the various immigration authorities in the past.

Sydney Opera House

Sydney Bondi Beach

In Sydney, we checked into the Pacific Hotel on the Bondi Beach for two nights. On the third day, we were told that our allowances had been paid into our bank accounts and we now had to pay our own way. We were advised to move into a cheaper accommodation nearby because we would not be able to afford the hotel charges. At the same time, we were taken around Sydney visiting various well-known tourist attractions, department stores, and banks. To familiarize us with the Australian way of life, we attended induction lectures which included Australian history, system of government, social etiquette and sports.

The Australian Colombo Plan Scholarship provided a generous financial package for the students. Besides a living allowance of twenty pounds per fortnight which was about the minimum wage for an Australian worker, the Australian Government also paid for return airfares once every three years from home country to Australia, all tuitions fees, the cost of textbooks and the cost of clothing. The going rate for full board (lodging and meals) in Sydney and Melbourne was about ten pounds a fortnight, thus leaving ten pounds for traveling and other expenses.

After staying in Sydney for one month, I transferred to Melbourne to enroll for my pre-university year. Entry to University of Melbourne was by competitive marks gained in the matriculation examination.

I was assigned a case manager regarding my academic study as well as my welfare including arranging for my board and lodging with Australian families. Because I was a mature student, I was enrolled at the Taylors College which catered mainly for repeat private school students. The college also had a number of mature students sponsored by various government departments, the armed forces, and private enterprises. Taylors College was a well-organized institution and the teachers were competent and experienced. I soon settled down to study and managed to pass my matriculation examination with good marks in English, physics, chemistry, and pure and applied mathematics qualifying me to undertake a degree course in Engineering.

ONE WEEK LIVING WITH AUSTRALIAN FARMING FAMILIES

Before I commenced my first Year at the university, my case manager arranged for me to spend one week living with a farming family, Mr. and Mrs. John Anderson, in Harrod in the Western District of Victoria. The District was settled by returned servicemen under the Soldier SettlementScheme and many had fought against the Japanese in Borneo during

Melbourne St. Kilda Beach

Melbourne City Southbank

the Second World War. Life was good for them as there was a strong demand for wool and the price of wool was historically high due to the Korean War. I took a train from Melbourne to Horsham

Compilation, photos, setting, layout and Written by Leong Chee Seng, 龍志成 22 January 2019

From the desk of the Editor: Please stay tune for more to continue soon. Please click to “follow” so that you will be notified automatically.

FOOTNOTE:

The author Leong Chee Seng, 龍志成 was among the first batch of students who graduated from Kuala Belait Chung Hua Primary School after the 2nd world war. For the story before St. Thomas’s School time, see “Memories of our venture to China for further education”

DISCLAIMER:

Some of the photos are from social media. Some of the images in this blog are copyright to the respective owners. Please let us know if you have any issues with copyright. Let us know and we will promptly remove them.C

email comment received from Mr. Chiew Chee Phoong 丘啓楓 :-

大致瀏覽一遍,内容非常精彩,歷史圖片非常珍貴。

LikeLiked by 1 person

啓楓 同学. 多谢您评论和赞扬. 我甚感欣慰和感激.

我中文不够标准. 只能用英语继续写作. 请多原谅.

Leong Chee Seng, 龍志成

LikeLike

I am a younger brother of Chee Seng.

I find it fascinating to read my brother’s latest article on “My time as Australian scholarship student”. Honestly, as siblings, we have had little ideas how each other grew up as we went on separate paths upon leaving home after our primary schooling !

My eldest brother, Chee Seng left home for Nanjing after completing his primary education in Kuala Belait Brunei. Believe it or not , all our 6 siblings could only be reunited once when our father passed away in Kuala Belait in December 1980!

My brother Chee Seng was lucky to win a schorlship to study in Australia and along with that granted a British Passport otherwise he would be a “Stateless person” in Brunei. Except our eldest brother Chee Seng all of us brothers and sisters were born in Brunei. We were all Stateless persons then because Brunei do not grant citizenship to non Malays born in the Sultanate ! That was why we, like most Chinese, all migrated overseas. I remember Chinese formed 25% of Brunei population of around 200,000 in 60s . Most Chinese migrated and I think currently Chinese has fallen below 10% in Brunei’s 400,000 inhabitants !

My brother surely has done very well. But he worked very hard and worked smart for it . He is a very determined person to overcome the many obstacles we have read about him. I am very proud to have him as a wonderful eldest brother that we can look up to as well an example to our children !

Finally I believe in fate ! I was awarded a schlorship to study engineering too. I was given the option to read laws in UK. But my mother objected to my second choice because she believed lawyers are injustice when they argue and let off criminals and hence this will bring misfortune to our household !!!

The most terrifying thing she believed was children of lawyers would be born with an ass!

My life profile would be totally different if I choose a different path and to remain in Brunei !

LikeLike

Thank you for your encouraging comment. Stay tune! Chee Seng will continue to write more to complete his Australian way of life during his studies in Melbourne. Please click “like” so that you might be notified when his next story been published…soon.

LikeLike

What an interesting post this is. Thank you for sharing your memories with us!

LikeLike

You are most welcome to read our eBook, Elena. Chee Seng has only written the first part of his life as a Australian Scholarship student. Stay tuner to his next chapter. Meanwhile please select “LIKE” so our system will notify you automatically when his new story is being published.

LikeLike

Wonderful reading! Thanks for sharing – what a great insight into how things were in 1956 in Australia especially during the hideous white Australia policy – glad he made it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a very inspiring story and serves as a timely reminder of how lucky our kids are to have the opportunity to study in Australia. What an amazing journey you have had Pa. We are all really looking forward to reading about your next adventure!

LikeLike

Really enjoyed your story and how you came to get a British passport. Keep up the great work.

LikeLike

I was born in China and had a passport issued by the Republic of China government when I together with 3 other school mates went to study in China in 1948. There was civil war and subsequently, the incumbent Republic of China government was overthrown by the communist People’s Republic of China. We had to leave China to return to Brunei just before the country was overrun. On transit in Singapore, our Chinese passports were no longer recognized by the Singapore Colonial government and we were regarded as stateless persons. Consequently, we were remanded in Singapore’s immigration jail. (Refer my previous post “Memories of our venture to China for further study”)

I wish all my readers Happiness and Prosperity in the Year of the Pig.

Leong Chee Seng, 龍志成

LikeLike

We welcome you to leave your comment “LEAVE A REPLY” . Please click “LIKE” if you enjoy reading the story. Thank you

LikeLike

啓楓 同学. 多谢您评论和赞扬. 我甚感欣慰和感激.

我中文不够标准. 只能用英语继续写作. 请多原谅.

As my Chinese is not up to scratch, I would have to continue my writing in English.

I thank my brother Siew Kong for his post and for being generous in his assessment of me.

I thank my daughters Elena and Wendy, Jody and Ruey for their comments and interest in my life story.

As my article is an abridged version, I stand to answer any questions my readers may have.

On her Facebook account, http://www.facebook.com/drakoncreative, one of Elena’s friends had asked how I ended up a stateless person.

I was born in China and had a passport issued by the Republic of China government when I together with 3 other school mates went to study in China in 1948. There was civil war and subsequently, the incumbent Republic of China government was overthrown by the communist People’s Republic of China. We had to leave China to return to Brunei just before the country was overrun. On transit in Singapore, our Chinese passports were no longer recognized by the Singapore Colonial government and we were regarded as stateless persons. Consequently, we were remanded in Singapore’s immigration jail. (Refer my previous post “Memories of our venture to China for further study”)

I wish all my readers Happiness and Prosperity in the Year of the Pig.

Leong Chee Seng, 龍志成

LikeLike

” Very impressive student story ” commented by. Dato Ahmad Matnor sent by email

LikeLike

Comment from Poh Eng Hong “Great piece of journey for this KB guy at your time”

LikeLike

Thank you Dato Ahmad Matnor and Mr Poh Eng Hong for your gracious comments .

Lady Luck did favour me to allow me to achieve some success in life.

Sorry for my late reply as I had not been well recently.

LikeLike